Glenda Merle (Kennedy) Taylor

- Glenda Merle was born on September 1, 1939 in Haskell, Texas and died on October 13, 1995. Married Alford Inman Taylor In October 1960.

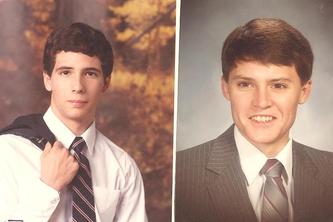

- Ben DavidTaylor was born on September 7, 1961 in Odessa, Texas. Married Susan Elise Durr on June 11, 1994. Divorced

- Jessica Elise was born September 22, 2004 in Dallas, Texas.

- Jessica Elise was born September 22, 2004 in Dallas, Texas.

- Allison Was born April 9, 1961 in Bay City, Texas. Married Lester Robert Blizzard on July 19, 1986.

- Taylor Williams was born on September 19, 1988 in Eastland, Texas. Married Elizabeth Ann Renteria on September 2018. Divorced. Married Vy on May 23, 2021.

- Rohan Al was born on april 15, 2020.

- Khan Dai was born on June 15, 2022.

- Rohan Al was born on april 15, 2020.

- Harry James was born on July 14, 1993 in Houston, Texas.

- Marie Elizabeth Lobos (Foster Child) was born on May 11, 1985 in Belize, South America. Married George Anthony Palau.

- Taylor Williams was born on September 19, 1988 in Eastland, Texas. Married Elizabeth Ann Renteria on September 2018. Divorced. Married Vy on May 23, 2021.

- James Kennedy was born on December 18, 1966 in Houston, Texas. Married Lou Ann (Cox) on September 1, 1990.

- Seth Kennedy was born on November 28, 1996 in Houston, Texas.

- Wade Mitchel was born on June 20, 1998 in Houston, Texas.

- Seth Kennedy was born on November 28, 1996 in Houston, Texas.

- Ben DavidTaylor was born on September 7, 1961 in Odessa, Texas. Married Susan Elise Durr on June 11, 1994. Divorced

I want to be the baby!

When Mary Jo and Jim found out they were to have twins, everyone was happy except for maybe one person, Glenda. Mary Jo said "Glenda kept hoping we would drop the twins on their heads, so she could be the baby of the family."

"I made a zero"-A little girl's song!

Lloyd, May 21, 1997

One day Glenda came home probably from the first or second grade. She was singing rather happily it seemed, although something had happened that day at school that might have made her unhappy. She wasn't bothered much by what had happened, apparently, as she was singing "I made a ze ro. I made a ze ro." to the tune of Sol Mi La Sol Mi. Sol Mi La Sol Mi.

One day Glenda came home probably from the first or second grade. She was singing rather happily it seemed, although something had happened that day at school that might have made her unhappy. She wasn't bothered much by what had happened, apparently, as she was singing "I made a ze ro. I made a ze ro." to the tune of Sol Mi La Sol Mi. Sol Mi La Sol Mi.

Death and suffering have their purpose!

On July 4, 2009, Allison wrote the following stirring words about her mom and the time surrounding Glenda's death in an email to Sandra Herod.

Hey, AUNT Sandra--my secretary/friend Susie has a mother-in-law who is dying from ovarian cancer. She and I have been talking about it, of course. I mentioned to her that the last days of death and suffering have their purpose too, and we talked about it for awhile. The she called me to write down my thoughts on the subject.

It became a much more personal (and longer) thing than she probably intended. In any case, I thought I'd send it to you, as one of the small circle of people who love my mother every day and forever.

July 4, 2009

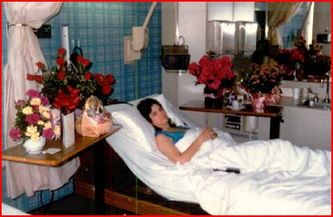

My mother died of ovarian cancer some years ago. She underwent chemotherapy and multiple surgeries, but eventually the doctors announced that there was nothing else they could co. She was sent home to die.

My mother was a Christian woman and was not afraid to die. She saw no point, however, in the waiting process, which bound to be unpleasant. Her attitude was that if she could just know "I'll die tomorrow," she would be OK with it.

That, of course, was not to be. The doctors took her off all nutrition because tumors were blocking her bowels. In effect, she starved to death. It took about six weeks.

Starving to death was not, strangely enough, painful in and of itself. During that time, however her tumors continued to grow, as did her pain. Her hospice care provider, Joe, provided us with morphine for pain. The medication was in the form of an IV drip for pain management and a liquid to put under her tongue for acute pain. Joe also let us know that the morphine could kill her, if we upped the dosage – and that some families, impatient with the process, quietly and without fuss turn up the dosage and speed up the process.

He also told us something else which we did not quite internalize at the time. He said that the last days of life, the suffering, the waiting, served a purpose.

We waited. We served my mother through her final days until the last. SHE waited. She took each day as it came and loved us to the end. And the end came, of course, and one day she took her final breath.

When we looked back, we realized that the final days did, indeed, have a purpose. My father, my brothers and I came together to care for my mother. Each of us had our jobs and our shifts, day and night. We cleaned her wounds and cleaned out her IV ports. We administered her pain medications and brought her ice chips to chew. We bathed her and brushed her hair. No stranger's hand touched her from the time she came home to her death. One or more of us stayed with her at all times, day and night.

At first she was conscious all normal hours. We could talk to her about everything. She helped us prepare for her own death. Her faith began and remained strong. My mother was not much of a preacher. She just had quiet, matter-of-fact confidence in the mercy of her Lord. "I know the Lord will find a way for me" was perhaps her favorite song, and she sang it and believed in it. "If I walk in Heaven's light, shun the wrong and do the right, I know the Lord will find a way for me."

She planned her own funeral with us, too. We would lay on her bed with pen and paper in hand and plan who would lead songs, and what songs they would sing, and who would read the prayers. Then we all sat around her bed and sang the songs she chose together. No, my mother was not afraid to die, thank God.

Eventually her hours of consciousness grew less and her pain grew more. We went from unconsciousness to moments when we would look up and see her eyes open and on us, and she would say "I love you," before unconsciousness took her again.

Eventually, there was a day with more consciousness than usual, when she told me that she thought she would die that day. She had me kneel beside the bed and she prayed for us. She prayed that God watch her family and see them again in Heaven, and she prayed that God come quickly for her.

She did not die, however, not that day. Instead she had a series of seizures, eyes rolling back in her bed, body rigid and, horrifyingly enough, tongue caught between her teeth and blood seeping out. We didn't let that happen again. Instead, my sister-in-law and I spent one night crouched by her side, watching her face for signs of the next seizure. Then we would know to pounce on her and get a wooden spoon between her teeth before her jaws clamped down once again and the shaking started.

That was a long night. She never really gained consciousness again. Instead she seemed to go into a sort of a coma. Her body felt rigid and unyielding to the touch. We still bathed her everyday and cleansed her wounds, but only her breath told us she was still alive.

Finally her breath, too, failed to be quite such a sure indicator of life. She would stop breathing altogether for a minute or more at a time. Many hours we spent, one by one, with our hands on her chest, waiting for the elusive breath to come. Days passed.

One night, after I had gone home for the evening and my brother and his wife had come for the night, the phone rang. My brother informed me that my mother had not breathed for more than five minutes. The end had come.

That night my family gathered together, we veterans of the last long weeks. We toasted each other and we toasted her life and her death. As time went on, we had the long leisure to consider whether Joe was right; whether those last days had, indeed, served a purpose.

Praise God, they had! Pain and suffering had done its job. They had weaned my mother away from life and made death a mercy, not a horror. When death came, my mother was ready to die.

And perhaps even more importantly, my mother's last days had drawn us together more than any other event in our lives, and we were already a close family. We did not spend our days in misery or fear, but in companionship and mutual service. How many hours did my brother and I spend lying down side by side doing the cross-word puzzle together in the sunshine of my mother's room, with her unconscious form on the bed beside us! All things made way for our shared love of our mother, the most important woman in the world to us. We learned to live in the moment. We really did not suffer from the thought of her eminent death, because right then she was alive and there was work to be done. We stopped everything to join in her final days of death.

Also her final hours were opportunities for all her friends, specifically her many church friends, to gather around her. Everyone wanted to help, everyone wanted to serve. The real problem was that we had so little for them to do. We jealously guarded our time with our mother and wanted no "relief" from her 24-hour care. So they sent cards. Mail call was a big event every day. Daddy would sit on the bed when my mother was awake and open an impressive stack of mail every day. We used to joke that if each person would have enclosed a dollar with each card, we could retire.

They brought food, as well. Oh, did they bring food! Little old ladies came with casseroles and pies. Businessmen in Mercedes pulled up at the door with marinated meats and dainty side-dishes. If we had had any decency we would have opened a soup kitchen. We never turned down the food, though, because it was people's way to show their love for my mother who had always shown love in action to those around her.

Those final days when we knew she was dying gave time for many people to say goodbye, each with their own privacy. Her many brother and sisters came into town, singly and in groups, to cuddle close to their beloved sister one more time. Many of her nieces and nephews came, too, to hug their Aunt Glenda and tell her what she had meant to them. People from all over her life checked in, from childhood friends to old boyfriends to her current circle of people. Each needed and wanted time with her, and each had time.

Death and suffering focused us all. Life became very simple and pure. As her hours of consciousness lessened, all lesser things fell away. "I love you" became the only words she would say in her few minutes of consciousness, and when her voice could no longer say it her eyes could. Irritations, details, annoyances, trivialities were burned way by those days of death and suffering, leaving only the pure gold of love.

Lastly, for those of us closest to her, her last days of suffering and death proved to us that faith can hold on to the end. She faced her death with trust in her Maker and love for her family. She never "clutched.” Although death was, on a basic level, incomprehensible to her as a human being, she knew God in whom she believed and "was persuaded that He is able to keep that which I've committed unto Him against that day."

May that day come quickly, when I can see my Maker and my mother once more!

Allison, May 7, 2010

That essay talks about how she died, but didn't she live well, too . . . there's a reason I call her the most important woman in the world. She was a woman of action, a problem solver, a sturdy, strong woman of God who moved on a straight-forward path and always did her duty. What a woman to have as a mother!

Hey, AUNT Sandra--my secretary/friend Susie has a mother-in-law who is dying from ovarian cancer. She and I have been talking about it, of course. I mentioned to her that the last days of death and suffering have their purpose too, and we talked about it for awhile. The she called me to write down my thoughts on the subject.

It became a much more personal (and longer) thing than she probably intended. In any case, I thought I'd send it to you, as one of the small circle of people who love my mother every day and forever.

July 4, 2009

My mother died of ovarian cancer some years ago. She underwent chemotherapy and multiple surgeries, but eventually the doctors announced that there was nothing else they could co. She was sent home to die.

My mother was a Christian woman and was not afraid to die. She saw no point, however, in the waiting process, which bound to be unpleasant. Her attitude was that if she could just know "I'll die tomorrow," she would be OK with it.

That, of course, was not to be. The doctors took her off all nutrition because tumors were blocking her bowels. In effect, she starved to death. It took about six weeks.

Starving to death was not, strangely enough, painful in and of itself. During that time, however her tumors continued to grow, as did her pain. Her hospice care provider, Joe, provided us with morphine for pain. The medication was in the form of an IV drip for pain management and a liquid to put under her tongue for acute pain. Joe also let us know that the morphine could kill her, if we upped the dosage – and that some families, impatient with the process, quietly and without fuss turn up the dosage and speed up the process.

He also told us something else which we did not quite internalize at the time. He said that the last days of life, the suffering, the waiting, served a purpose.

We waited. We served my mother through her final days until the last. SHE waited. She took each day as it came and loved us to the end. And the end came, of course, and one day she took her final breath.

When we looked back, we realized that the final days did, indeed, have a purpose. My father, my brothers and I came together to care for my mother. Each of us had our jobs and our shifts, day and night. We cleaned her wounds and cleaned out her IV ports. We administered her pain medications and brought her ice chips to chew. We bathed her and brushed her hair. No stranger's hand touched her from the time she came home to her death. One or more of us stayed with her at all times, day and night.

At first she was conscious all normal hours. We could talk to her about everything. She helped us prepare for her own death. Her faith began and remained strong. My mother was not much of a preacher. She just had quiet, matter-of-fact confidence in the mercy of her Lord. "I know the Lord will find a way for me" was perhaps her favorite song, and she sang it and believed in it. "If I walk in Heaven's light, shun the wrong and do the right, I know the Lord will find a way for me."

She planned her own funeral with us, too. We would lay on her bed with pen and paper in hand and plan who would lead songs, and what songs they would sing, and who would read the prayers. Then we all sat around her bed and sang the songs she chose together. No, my mother was not afraid to die, thank God.

Eventually her hours of consciousness grew less and her pain grew more. We went from unconsciousness to moments when we would look up and see her eyes open and on us, and she would say "I love you," before unconsciousness took her again.

Eventually, there was a day with more consciousness than usual, when she told me that she thought she would die that day. She had me kneel beside the bed and she prayed for us. She prayed that God watch her family and see them again in Heaven, and she prayed that God come quickly for her.

She did not die, however, not that day. Instead she had a series of seizures, eyes rolling back in her bed, body rigid and, horrifyingly enough, tongue caught between her teeth and blood seeping out. We didn't let that happen again. Instead, my sister-in-law and I spent one night crouched by her side, watching her face for signs of the next seizure. Then we would know to pounce on her and get a wooden spoon between her teeth before her jaws clamped down once again and the shaking started.

That was a long night. She never really gained consciousness again. Instead she seemed to go into a sort of a coma. Her body felt rigid and unyielding to the touch. We still bathed her everyday and cleansed her wounds, but only her breath told us she was still alive.

Finally her breath, too, failed to be quite such a sure indicator of life. She would stop breathing altogether for a minute or more at a time. Many hours we spent, one by one, with our hands on her chest, waiting for the elusive breath to come. Days passed.

One night, after I had gone home for the evening and my brother and his wife had come for the night, the phone rang. My brother informed me that my mother had not breathed for more than five minutes. The end had come.

That night my family gathered together, we veterans of the last long weeks. We toasted each other and we toasted her life and her death. As time went on, we had the long leisure to consider whether Joe was right; whether those last days had, indeed, served a purpose.

Praise God, they had! Pain and suffering had done its job. They had weaned my mother away from life and made death a mercy, not a horror. When death came, my mother was ready to die.

And perhaps even more importantly, my mother's last days had drawn us together more than any other event in our lives, and we were already a close family. We did not spend our days in misery or fear, but in companionship and mutual service. How many hours did my brother and I spend lying down side by side doing the cross-word puzzle together in the sunshine of my mother's room, with her unconscious form on the bed beside us! All things made way for our shared love of our mother, the most important woman in the world to us. We learned to live in the moment. We really did not suffer from the thought of her eminent death, because right then she was alive and there was work to be done. We stopped everything to join in her final days of death.

Also her final hours were opportunities for all her friends, specifically her many church friends, to gather around her. Everyone wanted to help, everyone wanted to serve. The real problem was that we had so little for them to do. We jealously guarded our time with our mother and wanted no "relief" from her 24-hour care. So they sent cards. Mail call was a big event every day. Daddy would sit on the bed when my mother was awake and open an impressive stack of mail every day. We used to joke that if each person would have enclosed a dollar with each card, we could retire.

They brought food, as well. Oh, did they bring food! Little old ladies came with casseroles and pies. Businessmen in Mercedes pulled up at the door with marinated meats and dainty side-dishes. If we had had any decency we would have opened a soup kitchen. We never turned down the food, though, because it was people's way to show their love for my mother who had always shown love in action to those around her.

Those final days when we knew she was dying gave time for many people to say goodbye, each with their own privacy. Her many brother and sisters came into town, singly and in groups, to cuddle close to their beloved sister one more time. Many of her nieces and nephews came, too, to hug their Aunt Glenda and tell her what she had meant to them. People from all over her life checked in, from childhood friends to old boyfriends to her current circle of people. Each needed and wanted time with her, and each had time.

Death and suffering focused us all. Life became very simple and pure. As her hours of consciousness lessened, all lesser things fell away. "I love you" became the only words she would say in her few minutes of consciousness, and when her voice could no longer say it her eyes could. Irritations, details, annoyances, trivialities were burned way by those days of death and suffering, leaving only the pure gold of love.

Lastly, for those of us closest to her, her last days of suffering and death proved to us that faith can hold on to the end. She faced her death with trust in her Maker and love for her family. She never "clutched.” Although death was, on a basic level, incomprehensible to her as a human being, she knew God in whom she believed and "was persuaded that He is able to keep that which I've committed unto Him against that day."

May that day come quickly, when I can see my Maker and my mother once more!

Allison, May 7, 2010

That essay talks about how she died, but didn't she live well, too . . . there's a reason I call her the most important woman in the world. She was a woman of action, a problem solver, a sturdy, strong woman of God who moved on a straight-forward path and always did her duty. What a woman to have as a mother!

A sister and a friend

Glenda: What can I say? She and I were so close that when we talked several mornings a week that we didn't even have to stop and say what we were thinking about--just started talking in the middle of our thoughts. It was like we were on the same wave link. Bill just would say, "Can't you even say hello?" I told him it was not necessary. She knew where I was coming from.

From the time she was little, she was a one and only. Mother would say, "You girls (Edna and I) need to help her with her homework." She did not need any help! She was smarter and quicker than either one of us, but she had that deal figured out. She would curl up and take a nap while we helped her.

When it was time for Glenda to go to college, she said she would not go unless she could room with me. That was no problem. I was a "checker" at McKenzie Dorm at Abilene Christian and felt great because it paid for my room and board, but even felt better that I had a private bath and a larger room. We roomed together, but she and I had different friends. She liked the football guys. She and her friend, Merle Woody, had a good time. I majored in business education, so Glenda majored in business education. She and Bill were quite a pair! They preferred going out to eat to studying. Of course, I had to go also. But they had the advantage of having my notes on the classes. They did as well as I did, but both of them were smart.

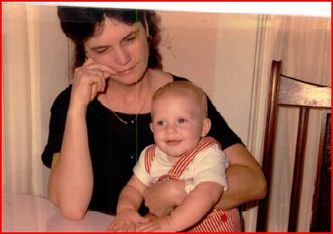

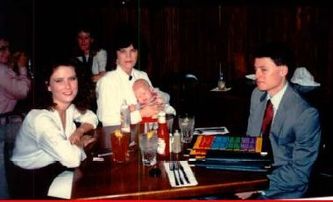

Bill and I went to Odessa to visit Glenda and Al when Diana was just nearly a year old--just in time for Glenda to go into labor with Ben. He was born on September 7, 1961. We didn't stay long, as I remember. When Jim was born, my children and I went to help out. My memory of that time is that she was feeding Jim by the bottle. While I was doing some laundry, I left the nipples on the stove to sterilize--BUT the water boiled away and the nipples burned. Did you know that burning rubber stinks--bad!

We traveled together some, and one trip to Cimmeron, New Mexico, is vivid in my memory. Glenda was a good cook, and we had good food on that trip including French doughnuts! While we read our books, Al took about 5 of the children mountain climbing. He tied them together by ropes so they would not fall. We had good times.

And for the information of all of you who may be reading this, Glenda was the big help and driving force in keeping our family reunions together. She and I both wanted our families to remain close, and to do that, we had to get together once in awhile.

Of course, my memories of Glenda's last months are still tender with me after 15 years. She and Al went to Kentucky to see Al's sisters at school break. Glenda had an obstruction and had to have emergency surgery. That was on December 8, 1994--Jim's birthday. When she came out of surgery, she asked Al what kind of cancer she had. He tried to evade the question by saying the doctor wanted to talk to her. She told him that she had not been married to that doctor 30 years and she wanted to know what kind of cancer she had! When she called to tell me, she said different people had different chances for survival. I told her she had her work cut out for her--get busy and beat that cancer.

Sometime after her first treatment (I think it was), she and Al were here and were going to see Mother a last time. She got up and said she had a terrible headache. She thought maybe washing her hair would help. When she came back in the den holding a double handful of hair, she said "I thought I was ready for this." But she and I both were crying. I cry now even just remembering it. I thought I couldn't stand it, but even then she was thinking of me and my feelings. As hard as it is to believe, even when she was talking about her death, she asked me if I would be okay. There wouldn't be a body because she had donated her body to science. Can you believe that she was thinking of me? I couldn't.

I well remember the day she called (Allison dialed) both me and Betsy, I think. She said she thought that was the day! She couldn't control her hands. It wasn't the day, but oh, what a hard day it was.

I was there when she gave her jewelery and furs to Allison, Lou Ann, and Susan. It was a very tender time. But all those kids were wonderful during the time of her treatments. I have often said that Glenda not only taught us how to live, but also how to die. The kids gave her every attention possible to make those last days better. When I would express my grief, Allison would say we will live while she lives and grieve when she dies. Those kids were great as was Al.

From the time she was little, she was a one and only. Mother would say, "You girls (Edna and I) need to help her with her homework." She did not need any help! She was smarter and quicker than either one of us, but she had that deal figured out. She would curl up and take a nap while we helped her.

When it was time for Glenda to go to college, she said she would not go unless she could room with me. That was no problem. I was a "checker" at McKenzie Dorm at Abilene Christian and felt great because it paid for my room and board, but even felt better that I had a private bath and a larger room. We roomed together, but she and I had different friends. She liked the football guys. She and her friend, Merle Woody, had a good time. I majored in business education, so Glenda majored in business education. She and Bill were quite a pair! They preferred going out to eat to studying. Of course, I had to go also. But they had the advantage of having my notes on the classes. They did as well as I did, but both of them were smart.

Bill and I went to Odessa to visit Glenda and Al when Diana was just nearly a year old--just in time for Glenda to go into labor with Ben. He was born on September 7, 1961. We didn't stay long, as I remember. When Jim was born, my children and I went to help out. My memory of that time is that she was feeding Jim by the bottle. While I was doing some laundry, I left the nipples on the stove to sterilize--BUT the water boiled away and the nipples burned. Did you know that burning rubber stinks--bad!

We traveled together some, and one trip to Cimmeron, New Mexico, is vivid in my memory. Glenda was a good cook, and we had good food on that trip including French doughnuts! While we read our books, Al took about 5 of the children mountain climbing. He tied them together by ropes so they would not fall. We had good times.

And for the information of all of you who may be reading this, Glenda was the big help and driving force in keeping our family reunions together. She and I both wanted our families to remain close, and to do that, we had to get together once in awhile.

Of course, my memories of Glenda's last months are still tender with me after 15 years. She and Al went to Kentucky to see Al's sisters at school break. Glenda had an obstruction and had to have emergency surgery. That was on December 8, 1994--Jim's birthday. When she came out of surgery, she asked Al what kind of cancer she had. He tried to evade the question by saying the doctor wanted to talk to her. She told him that she had not been married to that doctor 30 years and she wanted to know what kind of cancer she had! When she called to tell me, she said different people had different chances for survival. I told her she had her work cut out for her--get busy and beat that cancer.

Sometime after her first treatment (I think it was), she and Al were here and were going to see Mother a last time. She got up and said she had a terrible headache. She thought maybe washing her hair would help. When she came back in the den holding a double handful of hair, she said "I thought I was ready for this." But she and I both were crying. I cry now even just remembering it. I thought I couldn't stand it, but even then she was thinking of me and my feelings. As hard as it is to believe, even when she was talking about her death, she asked me if I would be okay. There wouldn't be a body because she had donated her body to science. Can you believe that she was thinking of me? I couldn't.

I well remember the day she called (Allison dialed) both me and Betsy, I think. She said she thought that was the day! She couldn't control her hands. It wasn't the day, but oh, what a hard day it was.

I was there when she gave her jewelery and furs to Allison, Lou Ann, and Susan. It was a very tender time. But all those kids were wonderful during the time of her treatments. I have often said that Glenda not only taught us how to live, but also how to die. The kids gave her every attention possible to make those last days better. When I would express my grief, Allison would say we will live while she lives and grieve when she dies. Those kids were great as was Al.

Prayer and hope

Allison May 21, 1997

Steve Sandifer was a dear Christian friend of my mother. Once when she was upset about something she told me that she was going to talk to Steve, because she knew he would get down on his knees and pray with her.

I'm having the blues about my mother these days. It comes in spurts and in waves, and I'm beginning to recognize it. Probably if I read one of the books on mourning I would recognize many things. but a sort of pride keeps me away from such books. I suppose everyone likes to think their own grief is something special and unique.

But I miss her terribly, and I hate it for my kids and for Seth. Taylor keeps a picture collage of his grandmother by his bed, and talks to her regularly. It's an appropriate tribute, she loved him dearly.

You remember the day she called from the house for you (Sandra) and Aunt Betsy to come to her? She got scared that day, for really the first time, and she needed her big brother and sister. My Aunt Betsy amazes me. I remember her that day, in all her womanliness and strength. She could let my mother lean on her, could pet her and stroke her in the face of the terrible fear. I want to grow up like that.

Steve Sandifer was a dear Christian friend of my mother. Once when she was upset about something she told me that she was going to talk to Steve, because she knew he would get down on his knees and pray with her.

I'm having the blues about my mother these days. It comes in spurts and in waves, and I'm beginning to recognize it. Probably if I read one of the books on mourning I would recognize many things. but a sort of pride keeps me away from such books. I suppose everyone likes to think their own grief is something special and unique.

But I miss her terribly, and I hate it for my kids and for Seth. Taylor keeps a picture collage of his grandmother by his bed, and talks to her regularly. It's an appropriate tribute, she loved him dearly.

You remember the day she called from the house for you (Sandra) and Aunt Betsy to come to her? She got scared that day, for really the first time, and she needed her big brother and sister. My Aunt Betsy amazes me. I remember her that day, in all her womanliness and strength. She could let my mother lean on her, could pet her and stroke her in the face of the terrible fear. I want to grow up like that.

Taylor Blizzard story

Candlelight Church of Christ supports a missionary in the Philippines. The missionary came to speak at our church one night. His complexion was dusky and his face had a slight Asian cast to it. Taylor noticed the foreign tang and the following conversation ensued:

Taylor: "Mother is he from China?"

Allison "No,Taylor he's a missionary from the Philippines."

Taylor "Gee he must be awfully sorry that Goliath lost!"

Taylor: "Mother is he from China?"

Allison "No,Taylor he's a missionary from the Philippines."

Taylor "Gee he must be awfully sorry that Goliath lost!"

Al Taylor's Memories: Sent to Allison Blizzard March 21, 2023

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ALFORD INMAN TAYLOR

March 21, 2023

Dad gave me this the other day. He certainly didn’t write it recently, as now he only writes in block print. He doesn’t recall when he wrote it. But here goes (Allison Taylor Blizzard):

What is an autobiography? Can one actually write an appropriate story of one’s own life? Perhaps not. What follows is my story, as I remember it.

Born on August 13, 1931, in Manning, Angelina County, Texas I have no real recollection of life there. The last of eight children of Ben (Benjamin Earl) and Elizabeth Olive Bayne Taylor, I was told of the tragic death of child seven, Earl Bayne, many years later. He died of upper respiratory problems on November 28, 1931 in his mother’s arms, not yet three.

My father, pulled out of public school in maybe the seventh grade to help his father Hillary Taylor haul trees, showed promise as a debater. Maybe it was about this time that my father tried to defend his mother and was choked by his drunken father. Grandmother Taylor then divorced Granddad Taylor—a remarkable thing then. Dad never drank any alcoholic beverage and never allowed any in his home. [NOTE: This contradicts a memory of mine concerning the death of Earl Bayne. I seem to remember being told that when Earl Bayne was sick and dying, Granddad was away from the home on a drunken bender. But what do I know? ATB.]

Dad, a registered pharmacist grandfather in because he was then currently filling prescriptions, waw the storekeeper at the company store in Manning, a small town with only one industry, a sawmill with five planers running maybe 24-6.

Mother had a high school degree and some kind of teacher’s certificate. She and Dad were strong believers in education.

The family consisted, originally, of five girls and three boys. The other surviving boy contracted the terrible 1918 flu and was left with sleeping sickness and problems with muscle control. [Once again, this contradicts my memory; I thought he had St. Louis Encephalitis. ATB] He went to some college, served in the CCC and worked some in cutting and hauling brush, but was never really independent of parental control and support.

The girls were different. Olive (“Sammy”), born 1912, graduated SHSTC and much later taught school and was a school counselor in junior high.

Edna May, born in 1916, was brilliant in college and was with the US Government in Washington, D.C. during WWII. She also homeschooled her four children, not by choice, later. Still later on she was an outstanding teacher in the Maryland school system.

Eva (“Jet”), born 1919, worked her way through SHSTC, UT Pharmacy School and the UT School of Medicine and went on to specialize in dermatology.

Elizabeth (“Lib), born 1922, got a master’s degree in advertising from UT and worked for some hears as a court reporter in Houston.

Ben Alice, born 1924, was president of the SHSTC student body in 1945.

The family’s stay in Manning ended in the summer of 1935. By that time the sawmill had had two big fires and Dad got a job at a drug store, King’s, in Huntsville. Quite a move. Huntsville, home to SHSTC, later to be SHU, and the Texas Prison System, where Dad hired on as their pharmacist in 1937 and stayed until 1965 when on his 80th birthday he was forced to retire.

The Huntsville Years, 1935-1948

My fourth birthday was in Huntsville. I recall that I got a special birthday gift, a real toy truck with four rubber wheels, from my Uncle Alvin and Aunt Mill. Now I have to go back a bit. Dad had a large family, two girls and three boys. He was born in 1885, the second child and oldest boy. Mother’s dad, Granddad Bayne, was truly remarkable. He was a deputy sheriff in Houston County (Crockett, Texas) serving under Sheriff Harvey Bayne, his older brother. They married sisters, producing many double first cousins.

When we first moved to Huntsville we lived in a rent house on Avenue L, about the 16 or 17 hundred block. Then we moved, soon, to another rent house on 10th Street, just down the hill from the prison. It was probably in 1937 when we rented and moved into 1401 14th ST. I had started school in 1937 and it was in the summer of 1840 when we moved to the farm three miles north of Huntsville on the old Midway Road. Elementary school was easy, so I did not ever study. Reading was so much fun the teacher had to stop me so someone else could read aloud. Maybe after so many bright, all “A” children, my father relaxed and I became an all-time “C” student.

It took me many ears to realize that my dad bought the farm for ME. He wanted me to learn about trees, birds, cows, horses, plows, harness, and not grow up a town boy.

World War II

I remember exactly where I was and who I was with on Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941. I was in the front yard at the farm visiting with my cousin, Al Jimmerson, when Dad called us in. They, the Jimmersons and all, were listening to the radio. Of course at age 10, I had no idea where Pearl Harbor was or what it all meant. I think it was the next day at school when I heard FDR’s “Day of Infamy” speech. Soon we were learning the profiles (?) of Japanese aircraft, the heroism of Colin Kelly, the need for waste kitchen fats, scrap metal, war bonds, etc. We all knew there was a war going on and the draft (“Selective Service”) was building the army, navy and marines, each with its own air force, to fight the Axis powers, Germany, Japan and Italy. The Doolittle air raid on Tokyo, the German U-Boats in the Atlantic and the Lend-Lease to Russia we learned about soon, but only much later, the Holocaust.

In 1948, in February I believe, I joined the Texas National Guard, changing the year of my birth to 1930. [Dad was actually born in 1931.] That June I graduated high school and Eva (“Jet”) graduated UT Medical School in Galveston. Dad, Mother and I attended her graduation and I will never, ever forget the valedictory speech.

The UT years, 1948 – 1956, were truly wonderful. In the summer of ’48 I worked at two jobs in Port Lavaca: Beyer and Smith Dredging Company and Continental Construction Company. I was fired from the first on a Friday and hired by the second the next Monday. Odd, since the first company owned the second. I worked as a welder’s helper and then as a kind of shallow-water diver. A strange accident almost cost me my right leg on the first job. The second ended a day or two after a falling board broke the middle three bones of my right foot.

In September, registration took about three days in and around Gregory Gym. I should have been on “schopro” [? School probation maybe?] after that semester, with one “c,” three “Ds” and one “F” (in chemistry – ending my pre-med dreams). Instead, I somehow got into Plan II (maybe Harry Ransom was involved) the next year. To earn my keep I worked at a little restaurant just west of campus called “John’s Idea.” I did dishwashing morning and noon and for some months, rode on the night run, delivering sandwiches, doughnuts, coffee, cold drinks, etc. to dorms and rooming houses, sometimes until 1:00 a.m. The first semester I lived in a rent house off of 31st St. owned by a single mother with an infant child and five or six male students in several rooms. The second semester I was in Dorm J of the PHA dorms, the “Paste Board Palaces on the banks of the Waller” built by the Navy during WWII.

My sophomore year I moved into Dorm C and got off into debate. I remember well the morning our history teacher passed out the first exam I had taken in Plan II. My grade was a 57. I figured that would be the end of my UT career. The teacher said that he was disappointed with the grades, that the average grade was 57! I was amazed. The other students in that room, maybe 100, had all been in the top 2 per cent of their high school classes. That semester I got into MICA, the Men’s Independent College Association. I was elected to the council and then Secretary. I kept good notes and in the election for president I got 12 votes but the other guy got 13. In my debate society, the James Stephen Hogg one, I was chosen “Best Individual Speaker of the Evening” in the only one we lost, to the girl’s club. And I was elected president of JSH and tossed into the fountain.

In the summer of 1949 I got a job in a cotton gin in El Campo. It had a sign: “El Campo Farmer’s Cooperative Gin Society, Inc., Pete Longwood, President.” An old high school frien, O’Neal Murray, and I went down together and worked 12 hour days from 5 p.m.to 5 a.m., six days a week, operating the two sucker pipes pulling cotton bolls from trucks and trailers into the gin.

My junior year I got into Dorm A and worked for Statewide Plat Company. I made little maps of proposed oil well sites to be presented to the Railroad Commission using a crazy machine that heated a kind of metal or lead powder onto paper to make a copy. The strange device had a stranger name on it: “XEROX.” I also worked as a tray carrier at the big cafeteria just off campus and lived at a house just north of campus, free, for keeping it clean. I recall using a medicine to keep awake studying. It made ordinary print appear edged in red. Dexidrine Sulphate. Halfway through that junior year I dropped out and worked for one year.

My first job that year was with a geophysical, or “doodlebug,” company. The work involved measuring off settings for drill sites and geophone “jugs,” drilling shallow holes (less than 100 feet), putting in the dynamite and hooking it up, installing the jugs and hooking them up and some folks worked in the recording truck. I was a jug hustler, a driller’s helper, a shooter’s helper, a surveyor’s helper and then a surveyor – using first an Alledade [?] and Plane Table and later a transit. I lost that job while working in Trinity Bay when the tower turned over and after awhile in the salt water holding onto the transit, I failed to put it into fresh water (from the cooler) as we rode home.

I then got a job with the Stanolind Oil in South Texas –Duval County—and wound up in Sterling, Kansas. On the way home I had a wreck off Highway 75 near Buffalo. I had been falling asleep at the wheel and about 6:00 a.m. I awoke going through a barbed wife fence and down a hill, through another fence and then hitting a plowed field and a 55-gallon drum leaning against a house. Soon a lady in a housecoat appeared and seemed upset. Then, perhaps noticing my bloody burst upper life, she said, “Would you like coffee?” It was wonderful.

Back at UT in the Spring of 1953 I moved into a rent house with Bill Perkins, who was halfway through law school, and completed the courses necessary for me to enter in September.

My first year was Torts (Green), Contracts (McCormick), Property (Fritz), and Procedure (Thoron). I lived in an apartment with other 1Ls east of the new law school and delivered, on foot, before school, the Austin American Statesman. After class I worked for the Texas Teachers Retirement System four hours a day.

I recall hearing “Look to each side of you in this class. One of these will probably be gone soon.” (49 per cent of us graduated.) Dean Green when he first called on me asked where I was from. Huntsville. He smiled and started to ask me one of the usual questions, but then said “But I suppose you have head this before.” And Greg Thor would say “Defendant smiled at me!” As he became agitated, someone, or he, would finally say, “Does not state a cause of action.”

Being perpetually broke, I applied for a loan from the Scarborough Loan Fund. The application queried: Why aren’t your parents supporting you? Or something like that. I wrote in: “It was not their idea for me to come here in the first place.” The loan was granted.

In the summer of 1954, after looking for work for over a week, I told my dad I could find nothing. Next day he said to talk to Mr. X at Boettcher’s Mill. I did and he hired me to work 60 hours a week at $.50 an hour at maybe the hottest, dirtiest and most dangerous job I ever had, cleaning up around the “Steam nigger.” After two weeks a job came open where a construction company out of Lufkin was building the new hospital for Huntsville. It paid $1.47 per hour, time and a half over 40 hours. I had to take that job. Sadly, I explained all this to Mr. X. His response: “Don’t you worry, boy. The Meskin I fired to give you that job was doing it better than you ever could.”

March 21, 2023

Dad gave me this the other day. He certainly didn’t write it recently, as now he only writes in block print. He doesn’t recall when he wrote it. But here goes (Allison Taylor Blizzard):

What is an autobiography? Can one actually write an appropriate story of one’s own life? Perhaps not. What follows is my story, as I remember it.

Born on August 13, 1931, in Manning, Angelina County, Texas I have no real recollection of life there. The last of eight children of Ben (Benjamin Earl) and Elizabeth Olive Bayne Taylor, I was told of the tragic death of child seven, Earl Bayne, many years later. He died of upper respiratory problems on November 28, 1931 in his mother’s arms, not yet three.

My father, pulled out of public school in maybe the seventh grade to help his father Hillary Taylor haul trees, showed promise as a debater. Maybe it was about this time that my father tried to defend his mother and was choked by his drunken father. Grandmother Taylor then divorced Granddad Taylor—a remarkable thing then. Dad never drank any alcoholic beverage and never allowed any in his home. [NOTE: This contradicts a memory of mine concerning the death of Earl Bayne. I seem to remember being told that when Earl Bayne was sick and dying, Granddad was away from the home on a drunken bender. But what do I know? ATB.]

Dad, a registered pharmacist grandfather in because he was then currently filling prescriptions, waw the storekeeper at the company store in Manning, a small town with only one industry, a sawmill with five planers running maybe 24-6.

Mother had a high school degree and some kind of teacher’s certificate. She and Dad were strong believers in education.

The family consisted, originally, of five girls and three boys. The other surviving boy contracted the terrible 1918 flu and was left with sleeping sickness and problems with muscle control. [Once again, this contradicts my memory; I thought he had St. Louis Encephalitis. ATB] He went to some college, served in the CCC and worked some in cutting and hauling brush, but was never really independent of parental control and support.

The girls were different. Olive (“Sammy”), born 1912, graduated SHSTC and much later taught school and was a school counselor in junior high.

Edna May, born in 1916, was brilliant in college and was with the US Government in Washington, D.C. during WWII. She also homeschooled her four children, not by choice, later. Still later on she was an outstanding teacher in the Maryland school system.

Eva (“Jet”), born 1919, worked her way through SHSTC, UT Pharmacy School and the UT School of Medicine and went on to specialize in dermatology.

Elizabeth (“Lib), born 1922, got a master’s degree in advertising from UT and worked for some hears as a court reporter in Houston.

Ben Alice, born 1924, was president of the SHSTC student body in 1945.

The family’s stay in Manning ended in the summer of 1935. By that time the sawmill had had two big fires and Dad got a job at a drug store, King’s, in Huntsville. Quite a move. Huntsville, home to SHSTC, later to be SHU, and the Texas Prison System, where Dad hired on as their pharmacist in 1937 and stayed until 1965 when on his 80th birthday he was forced to retire.

The Huntsville Years, 1935-1948

My fourth birthday was in Huntsville. I recall that I got a special birthday gift, a real toy truck with four rubber wheels, from my Uncle Alvin and Aunt Mill. Now I have to go back a bit. Dad had a large family, two girls and three boys. He was born in 1885, the second child and oldest boy. Mother’s dad, Granddad Bayne, was truly remarkable. He was a deputy sheriff in Houston County (Crockett, Texas) serving under Sheriff Harvey Bayne, his older brother. They married sisters, producing many double first cousins.

When we first moved to Huntsville we lived in a rent house on Avenue L, about the 16 or 17 hundred block. Then we moved, soon, to another rent house on 10th Street, just down the hill from the prison. It was probably in 1937 when we rented and moved into 1401 14th ST. I had started school in 1937 and it was in the summer of 1840 when we moved to the farm three miles north of Huntsville on the old Midway Road. Elementary school was easy, so I did not ever study. Reading was so much fun the teacher had to stop me so someone else could read aloud. Maybe after so many bright, all “A” children, my father relaxed and I became an all-time “C” student.

It took me many ears to realize that my dad bought the farm for ME. He wanted me to learn about trees, birds, cows, horses, plows, harness, and not grow up a town boy.

World War II

I remember exactly where I was and who I was with on Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941. I was in the front yard at the farm visiting with my cousin, Al Jimmerson, when Dad called us in. They, the Jimmersons and all, were listening to the radio. Of course at age 10, I had no idea where Pearl Harbor was or what it all meant. I think it was the next day at school when I heard FDR’s “Day of Infamy” speech. Soon we were learning the profiles (?) of Japanese aircraft, the heroism of Colin Kelly, the need for waste kitchen fats, scrap metal, war bonds, etc. We all knew there was a war going on and the draft (“Selective Service”) was building the army, navy and marines, each with its own air force, to fight the Axis powers, Germany, Japan and Italy. The Doolittle air raid on Tokyo, the German U-Boats in the Atlantic and the Lend-Lease to Russia we learned about soon, but only much later, the Holocaust.

In 1948, in February I believe, I joined the Texas National Guard, changing the year of my birth to 1930. [Dad was actually born in 1931.] That June I graduated high school and Eva (“Jet”) graduated UT Medical School in Galveston. Dad, Mother and I attended her graduation and I will never, ever forget the valedictory speech.

The UT years, 1948 – 1956, were truly wonderful. In the summer of ’48 I worked at two jobs in Port Lavaca: Beyer and Smith Dredging Company and Continental Construction Company. I was fired from the first on a Friday and hired by the second the next Monday. Odd, since the first company owned the second. I worked as a welder’s helper and then as a kind of shallow-water diver. A strange accident almost cost me my right leg on the first job. The second ended a day or two after a falling board broke the middle three bones of my right foot.

In September, registration took about three days in and around Gregory Gym. I should have been on “schopro” [? School probation maybe?] after that semester, with one “c,” three “Ds” and one “F” (in chemistry – ending my pre-med dreams). Instead, I somehow got into Plan II (maybe Harry Ransom was involved) the next year. To earn my keep I worked at a little restaurant just west of campus called “John’s Idea.” I did dishwashing morning and noon and for some months, rode on the night run, delivering sandwiches, doughnuts, coffee, cold drinks, etc. to dorms and rooming houses, sometimes until 1:00 a.m. The first semester I lived in a rent house off of 31st St. owned by a single mother with an infant child and five or six male students in several rooms. The second semester I was in Dorm J of the PHA dorms, the “Paste Board Palaces on the banks of the Waller” built by the Navy during WWII.

My sophomore year I moved into Dorm C and got off into debate. I remember well the morning our history teacher passed out the first exam I had taken in Plan II. My grade was a 57. I figured that would be the end of my UT career. The teacher said that he was disappointed with the grades, that the average grade was 57! I was amazed. The other students in that room, maybe 100, had all been in the top 2 per cent of their high school classes. That semester I got into MICA, the Men’s Independent College Association. I was elected to the council and then Secretary. I kept good notes and in the election for president I got 12 votes but the other guy got 13. In my debate society, the James Stephen Hogg one, I was chosen “Best Individual Speaker of the Evening” in the only one we lost, to the girl’s club. And I was elected president of JSH and tossed into the fountain.

In the summer of 1949 I got a job in a cotton gin in El Campo. It had a sign: “El Campo Farmer’s Cooperative Gin Society, Inc., Pete Longwood, President.” An old high school frien, O’Neal Murray, and I went down together and worked 12 hour days from 5 p.m.to 5 a.m., six days a week, operating the two sucker pipes pulling cotton bolls from trucks and trailers into the gin.

My junior year I got into Dorm A and worked for Statewide Plat Company. I made little maps of proposed oil well sites to be presented to the Railroad Commission using a crazy machine that heated a kind of metal or lead powder onto paper to make a copy. The strange device had a stranger name on it: “XEROX.” I also worked as a tray carrier at the big cafeteria just off campus and lived at a house just north of campus, free, for keeping it clean. I recall using a medicine to keep awake studying. It made ordinary print appear edged in red. Dexidrine Sulphate. Halfway through that junior year I dropped out and worked for one year.

My first job that year was with a geophysical, or “doodlebug,” company. The work involved measuring off settings for drill sites and geophone “jugs,” drilling shallow holes (less than 100 feet), putting in the dynamite and hooking it up, installing the jugs and hooking them up and some folks worked in the recording truck. I was a jug hustler, a driller’s helper, a shooter’s helper, a surveyor’s helper and then a surveyor – using first an Alledade [?] and Plane Table and later a transit. I lost that job while working in Trinity Bay when the tower turned over and after awhile in the salt water holding onto the transit, I failed to put it into fresh water (from the cooler) as we rode home.

I then got a job with the Stanolind Oil in South Texas –Duval County—and wound up in Sterling, Kansas. On the way home I had a wreck off Highway 75 near Buffalo. I had been falling asleep at the wheel and about 6:00 a.m. I awoke going through a barbed wife fence and down a hill, through another fence and then hitting a plowed field and a 55-gallon drum leaning against a house. Soon a lady in a housecoat appeared and seemed upset. Then, perhaps noticing my bloody burst upper life, she said, “Would you like coffee?” It was wonderful.

Back at UT in the Spring of 1953 I moved into a rent house with Bill Perkins, who was halfway through law school, and completed the courses necessary for me to enter in September.

My first year was Torts (Green), Contracts (McCormick), Property (Fritz), and Procedure (Thoron). I lived in an apartment with other 1Ls east of the new law school and delivered, on foot, before school, the Austin American Statesman. After class I worked for the Texas Teachers Retirement System four hours a day.

I recall hearing “Look to each side of you in this class. One of these will probably be gone soon.” (49 per cent of us graduated.) Dean Green when he first called on me asked where I was from. Huntsville. He smiled and started to ask me one of the usual questions, but then said “But I suppose you have head this before.” And Greg Thor would say “Defendant smiled at me!” As he became agitated, someone, or he, would finally say, “Does not state a cause of action.”

Being perpetually broke, I applied for a loan from the Scarborough Loan Fund. The application queried: Why aren’t your parents supporting you? Or something like that. I wrote in: “It was not their idea for me to come here in the first place.” The loan was granted.

In the summer of 1954, after looking for work for over a week, I told my dad I could find nothing. Next day he said to talk to Mr. X at Boettcher’s Mill. I did and he hired me to work 60 hours a week at $.50 an hour at maybe the hottest, dirtiest and most dangerous job I ever had, cleaning up around the “Steam nigger.” After two weeks a job came open where a construction company out of Lufkin was building the new hospital for Huntsville. It paid $1.47 per hour, time and a half over 40 hours. I had to take that job. Sadly, I explained all this to Mr. X. His response: “Don’t you worry, boy. The Meskin I fired to give you that job was doing it better than you ever could.”

Important Documents and Letters

| glenda_letter_1986.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1041 kb |

| File Type: | |